Introduction

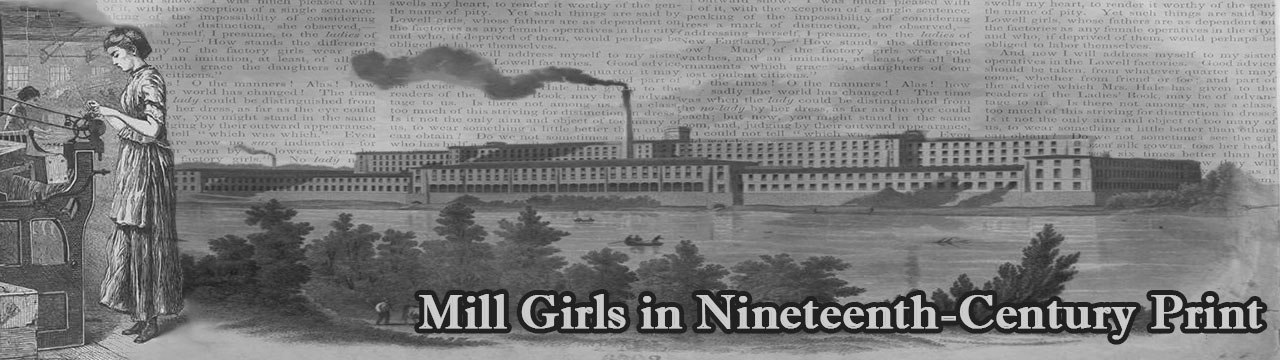

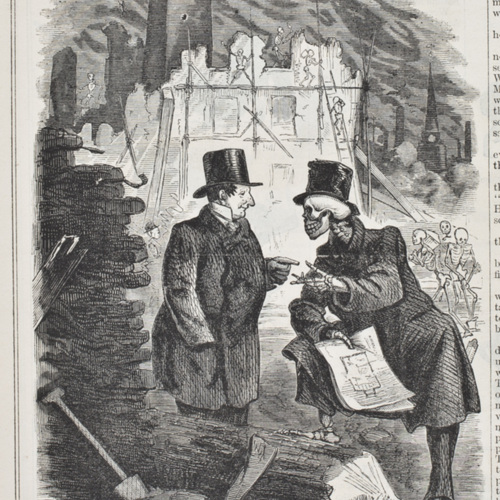

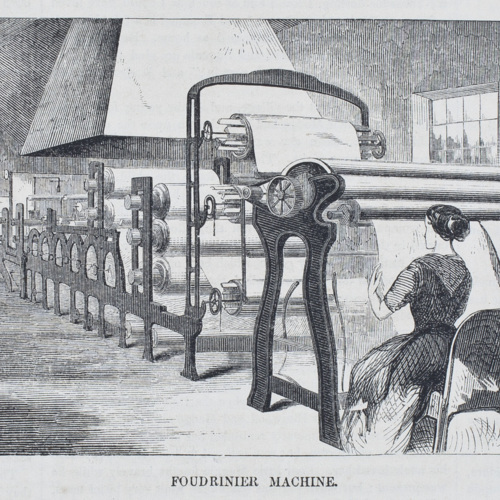

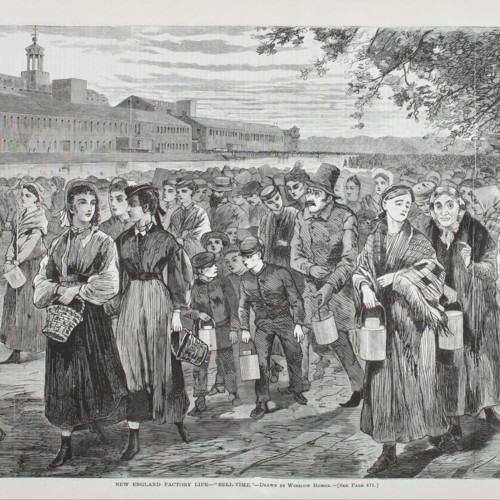

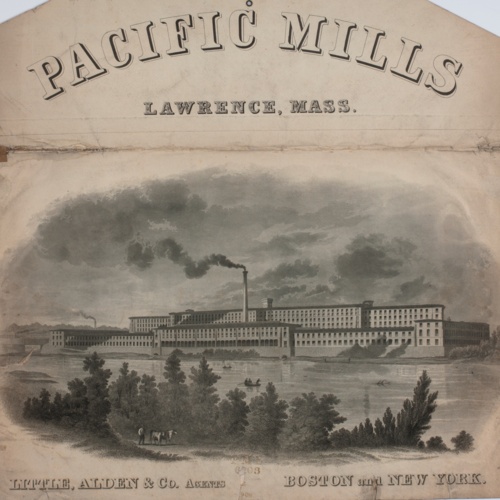

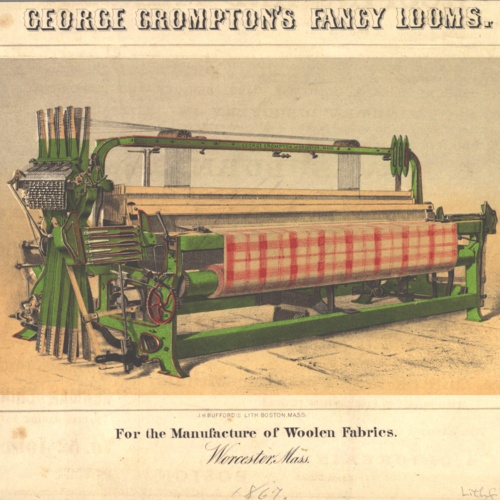

At the start of America’s industrial revolution, a large number of young women found employment and a unique form of independence in American textile mills. They first came from small farming towns to make a more lucrative living in places such as Lowell, Massachusetts, the center of the textile industry following initial mill construction in 1821. Later in the nineteenth century, women from Europe and Canada arrived in New England’s industrial towns, seeking what mill owners touted as a balanced life of work and leisure. These “mill girls,” as they came to be known, produced valuable cloth in massive quantity, and what they received in return was something of a double-edged sword. Through the independence offered by self-sustaining employment, they came into contact with commonly oppressive working environments, both dangerous and unfair. Yet, despite the power of the industrial machine and their diminutive name, the mill girls managed to form a coalition and community of their own in response. Though Lowell may be seen as the hub for mill girl culture and activism, the mill girls could be found across the mid-Atlantic and New England regions, where mills producing an enormous variety of product (cotton, wool, silk, canned goods, iron, etc.) sought a cheap and eager workforce.

At the start of America’s industrial revolution, a large number of young women found employment and a unique form of independence in American textile mills. They first came from small farming towns to make a more lucrative living in places such as Lowell, Massachusetts, the center of the textile industry following initial mill construction in 1821. Later in the nineteenth century, women from Europe and Canada arrived in New England’s industrial towns, seeking what mill owners touted as a balanced life of work and leisure. These “mill girls,” as they came to be known, produced valuable cloth in massive quantity, and what they received in return was something of a double-edged sword. Through the independence offered by self-sustaining employment, they came into contact with commonly oppressive working environments, both dangerous and unfair. Yet, despite the power of the industrial machine and their diminutive name, the mill girls managed to form a coalition and community of their own in response. Though Lowell may be seen as the hub for mill girl culture and activism, the mill girls could be found across the mid-Atlantic and New England regions, where mills producing an enormous variety of product (cotton, wool, silk, canned goods, iron, etc.) sought a cheap and eager workforce.

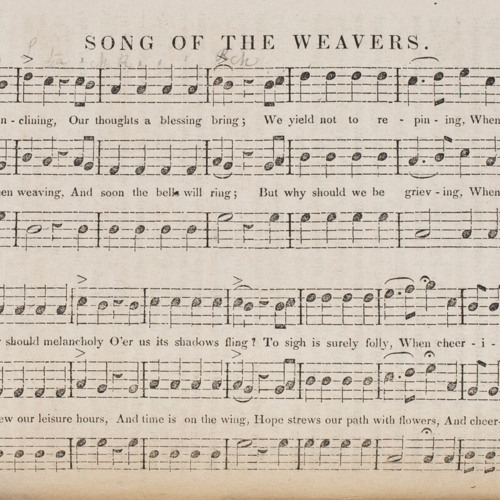

The popularity of the mill girl, in both word and image, came about in no small part due to their representation in print. This exhibition features items from newspaper and periodical publications, ranging from labor magazines such as the Man to literary monthlies such as Harper’s. Featuring selections both by and about the mill girls, from approximately 1834 to 1870, the exhibition highlights the culture and working conditions of the mills and the actions the women took to better their lives through self-advocacy.

Of course, no image of the past is ever fully complete. An anonymous mill girl, published in the Lowell Offering, does her best to describe “A Week in the Mill”:

The writer is aware that this sketch is an imperfect one. Yet there is very little variety in an operative’s life, and little difference between it and another life of labor. It lies ‘half in sunlight—half in shade.’ Few would wish to spend a whole life in a factory, and few are discontented who do thus seek a subsistence for a term of months or years.

That young women would choose such a life during this time in America’s history was surprising enough for many, and certainly profitable for the mill owners along Lowell’s overcrowded Merrimack River. Nevertheless, it is the community they formed during such unstable times and the stories unique among them that resonate beyond the factory walls.