What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

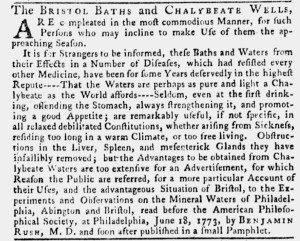

“These Baths and Waters … have been for some Years deservedly in the highest Repute.”

As spring gave way to summer in 1774, the proprietors of the “BRISTOL BATHS and CHALYBEATE WELLS” ran an advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette to advise residents of Philadelphia and other towns that they provided services “in the most commodious Manner, for such Persons who may incline to make Use of them [during] the approaching Season.” For any “Strangers” who were not familiar with “these Baths and Waters,” the proprietors proclaimed that they “have been for some Years deservedly in the highest Repute” for their “Effects in a Number of Diseases, which had resisted every other Medicine.” The chalybeate (or iron-infused) waters had a restorative effect that made visiting the spa an occasion for recuperation as well as relaxation. The proprietors provided several examples of maladies that the bathing in and drinking the chalybeate waters alleviated. They asserted that the waters strengthened the stomach, “promoting a good Appetite,” and rejuvenated “relaxed debilitated Constitutions, whether arising from Sickness, residing too long in a warm Climate, or too free living.” In addition, the iron-infused waters “have infallibly removed” “Obstructions in the Liver, Spleen, and mesenterick Glands.”

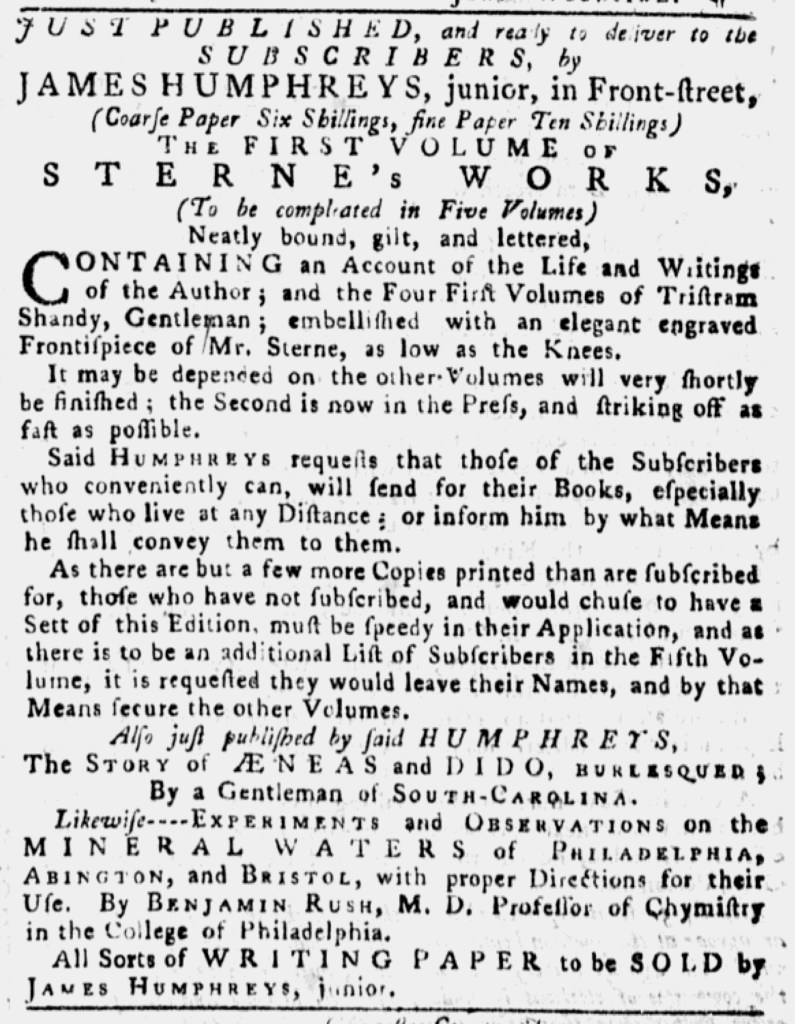

Yet the proprietors did not ask prospective patrons simply to take their word about the effects of the baths and wells in Bristol. Instead, they declared that the “Advantages to be obtained from Chalybeate Waters are too extensive for an Advertisement, for which Reason the Public are referred” to a pamphlet “by BENJAMIN RUSH, M.D.” The prominent physician had read a paper, “Experiments and Observations on the Mineral Waters of Philadelphia, Abington, and Bristol,” to the American Philosophical Society on June 18, 1773, and then published it. The proprietors of the Bristol Baths, Rush gave a more particular Account of their Uses, and the advantageous Situation of Bristol.” Historian Vaughan Scribner explains that Rush “nurtured colonists’ expanding interest in the science and commercialization of mineral springs.” The doctor provided a “general location and description of each spring,” described experiments with “mix[ing] more than twenty-one different substances with the mineral waters,” noted several diseases the waters cured (along with only a couple of exceptions), and “contended that the springs could hardly be rivaled for their health and commercial values.”[1] In the April 27 edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette, printer James Humphreys, Jr., conveniently placed an advertisement on the opposite side of the page as the notice about the Bristol Baths and Chalybeate Wells. Most of it concerned an update for subscribers to “STERNE’s WORKS,” but the printer appended a note that he sold “EXPERIMENTS and OBSERVATIONS on the MINERAL WATERS … By BENJAMIN RUSH, M.D. Professors of Chymistry in the College of Philadelphia.” Perhaps that was a happy coincidence for the proprietors of the Bristol Baths and Chalybeate Waters, but maybe they had coordinated with Humphreys to have their advertisements run at the same time. Either way, they did not direct the public to an obscure pamphlet. Instead, anyone interested in learning more could easily acquire Rush’s tract.

**********

[1] Vaughn Scribner, “‘The happy effects of these waters’: Colonial American Miner Spas and the British Civilizing Mission,” Early American Studies: An Interdisciplinary Journal 14, no. 3 (Summer 2016): 437, https://doi.org/10.1353/eam.2016.0020.